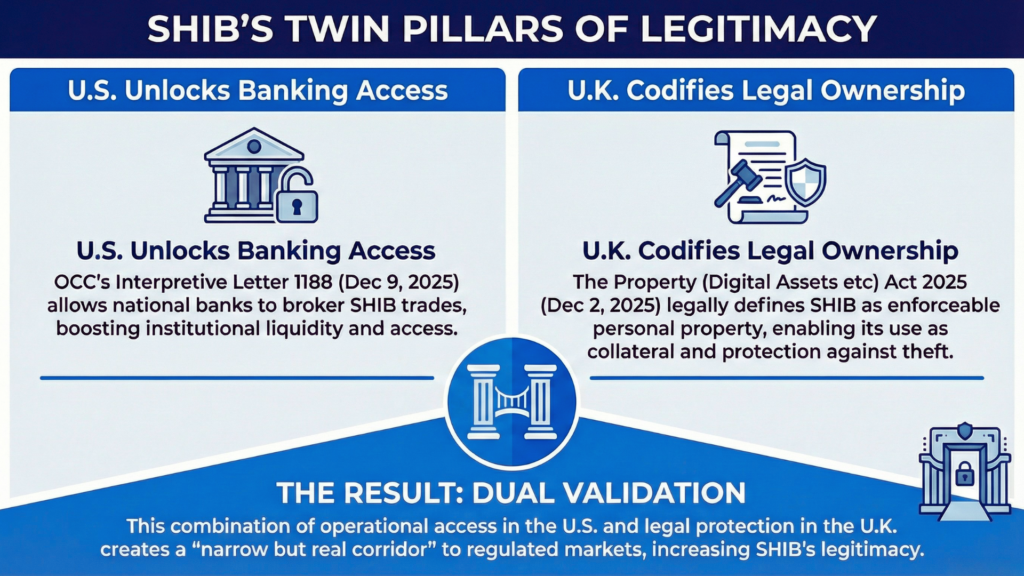

Washington and London, seven days apart in December 2025, handed Shiba Inu the clearest regulatory on-ramp in its history: the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency authorized U.S. national banks to broker SHIB trades under riskless principal rules, while the United Kingdom’s new Property Act explicitly recognized every Shiba Inu token as enforceable personal property under English law.

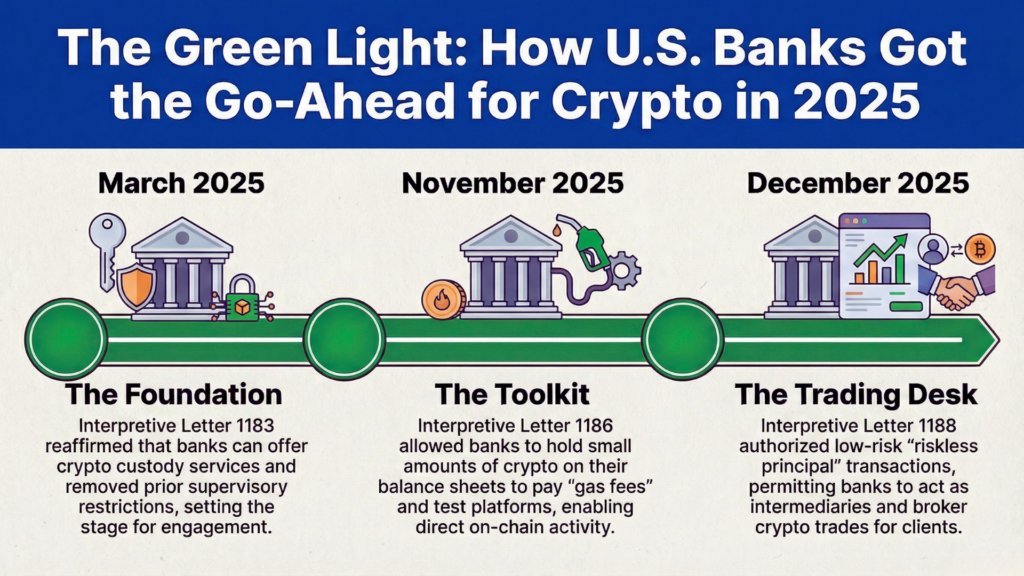

The letter arrived without ceremony. Stephen A. Lybarger, senior deputy comptroller, signed Interpretive Letter 1188 on a Monday morning in Washington.

Four pages, single-spaced, carried the weight of years of caution.National banks, the letter said, may now match buyers and sellers of cryptocurrency in the same heartbeat.

They hold nothing overnight. They assume almost no price risk.

They simply stand in the middle, collect a fee, and step aside. Shiba Inu appears nowhere in the document, yet every line applies to the dog-faced token with 589 trillion coins in circulation.

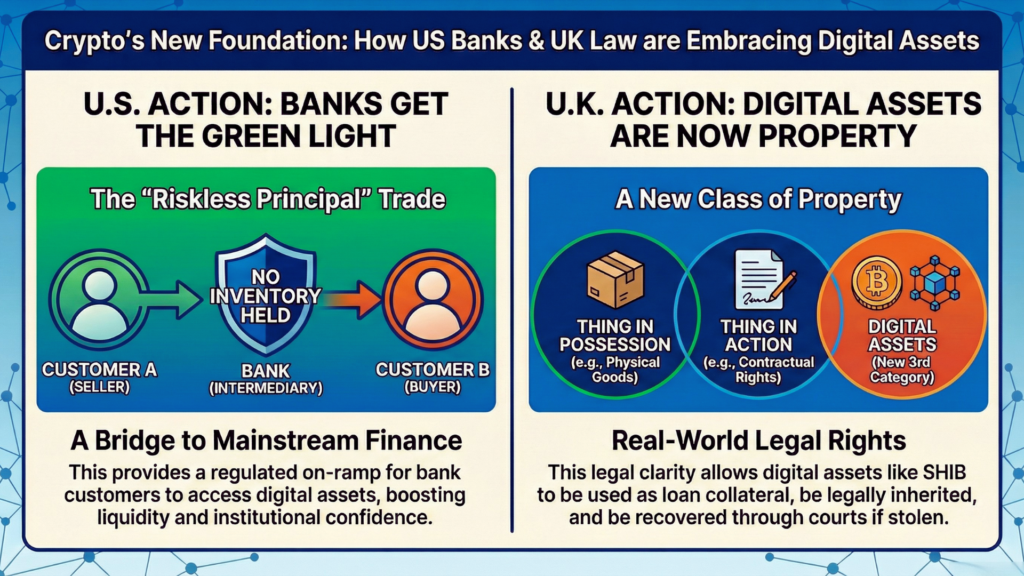

The OCC made the scope explicit. The activity is limited to riskless principal transactions: simultaneous offsetting purchases and sales for customers.

Banks do not take proprietary positions. They do not speculate.

They do not warehouse tokens. Settlement risk is the only material exposure, and even that is minimized by rapid liquidation procedures.

Because the bank never owns the asset, the trade avoids the heavy regulatory capital charges that would apply to inventory positions. Shiba Inu qualifies because the SEC has never classified it as a security.

The agency’s 2023 framework for meme coins, reiterated in public statements, treats tokens like Shiba Inu and Dogecoin, among others, as non-securities when they lack centralized profit expectations tied to the efforts of others. That status, while subject to change, keeps SHIB inside the perimeter the OCC just drew.

SEC-Statement-on-Meme-CoinAcross the Atlantic, another signature dried on parchment. King Charles III gave Royal Assent to the Property (Digital Assets etc) Act on December 2.

The statute runs to one page. It creates a third category of personal property, neither physical nor contractual, designed for items that exist only as private keys and ledger entries.

From that day forward, an English judge can freeze a SHB wallet the same way he once froze a bank account or a racehorse.

Related: Shiba Inu New Institutional, Global Frameworks Path in 2025

Inside the marble lobbies of regional banks, compliance officers began printing the new letter before noon. Fourteen applications for fresh national charters sat on desks at the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency.

Several carried business plans built around digital assets. Custody had been allowed for years. Stablecoin reserves too.

Now the last piece clicked into place, but only for matched client flow. The mechanics remain delicate.

A wealthy client in Ohio wants 50 million SHIB. A pension fund in Texas wants to sell the same amount.

The bank lines up the orders, pushes the dollars out, and sends the tokens back the other way. The whole thing settles so quickly that someone’s half-finished coffee is still warm.

No pile of assets waiting around, no lingering exposure, nothing that would trigger capital rules written for bonds and corn futures. This narrow lane is the entire point.

Proprietary trading in SHIB remains off-limits for national banks. Inventory positions would still draw punitive capital charges.

The OCC emphasized the distinction repeatedly: brokerage for customers, not speculation for the house.

In a wood-paneled courtroom off the Strand, a barrister opens a new precedent book. The Property Act sits beside Halsbury’s Laws of England, a slim addition with outsized reach.

A claimant seeks an injunction against a hacker who drained 300 million SHIB from a Manchester wallet. The judge grants the order the same afternoon.

Related: Banks Can Now Hold BONE for Shibarium Gas Fees

The tokens, now property under statute, stay frozen while lawyers argue ownership. The Act itself is foundational, not exhaustive.

It confirms digital assets belong to a third category of personal property. Courts will spend years mapping the exact boundaries: how security interests are perfected, how cross-border claims interact, whether the Financial Collateral Arrangements Regulations need amendment to capture tokenized assets cleanly.

HM Treasury has already signaled a review, but no timetable exists. For now, the statute gives English law what it lacked: certainty that SHIB can be owned, inherited, stolen, and recovered.

That alone unlocks doors for collateralized lending and tokenized real-world assets. The practical details will arrive case by case.

Washington and London moved in the same week, but they did not move in lockstep. The United States operates through a patchwork of regulators.

The OCC letter opens brokerage, yet broader market-structure clarity still waits on Congress. The CLARITY Act, expected for introduction in early 2026, aims to settle which tokens fall under which agency.

Until it passes, the entire banking pathway for SHIB rests on the SEC’s continued view that meme coins are not securities. One enforcement action or policy reversal could close the door the OCC just opened.

Britain chose a different architecture. The Financial Conduct Authority and Prudential Regulation Authority oversee a single, centralized regime.

That makes licensing cleaner, but it also means global firms must still translate U.S. brokerage permissions into U.K. compliance frameworks, and vice versa. Cross-border desks already speak of “regulatory arbitrage risk” when routing SHIB flow between the two jurisdictions.

In London, the Property Act is law, yet the practical machinery for collateral is not finished. The Law Commission recommended amendments to the Financial Collateral Arrangements Regulations so banks and funds can perfect security interests over digital assets without friction.

HM Treasury has the file. No public timetable exists.

Until those changes land, tokenized real-world assets backed by SHIB remain legally possible but operationally clunky for the largest institutions. These are not loopholes; they are the next chapters.

The corridor is open, but the paint is still wet.

Two documents now sit in ring binders across trading floors and law firms. They do not mention moonshots or diamond hands.

They speak in the measured language of risk limits and proprietary remedies. Together they draw a narrow but real corridor from a token launched in 2020 to the regulated capital markets of 2026.

Banks can match orders. Courts can freeze wallets.

The corridor is open, for now, and only as wide as the rules allow.

The dog walks on solid ground, but the ground can still shift.

Yona brings a decade of experience covering gaming, tech, and blockchain news. As one of the few women in crypto journalism, her mission is to demystify complex technical subjects for a wider audience. Her work blends professional insight with engaging narratives, aiming to educate and entertain.